Moving forward in Pittsburgh

The New Year started with a boom in Pittsburgh, and this period of calenderial transition portends more changes than usual. When I returned to Pittsburgh this past summer after an extended absence I had to steel myself for the changes wrought by the pandemic. It seemed unfathomable that a popular nightlife spot like Brillobox would close, or a hallowed neighborhood haunt like Take A Break would go for up for sale (however, the proximity of both these venues to Lawrenceville leads me to wonder how much the pandemic can be faulted, or whether the economic impacts of covid-19 only exacerbated the already established patterns of gentrification, capitalization, and dispossession…see also the massive new development taking shape on the former Penn Plaza site, a project that seems to have shifted from stalemate to speed train after the advent of coronavirus.). The closing days of 2021 saw similarly unthinkable news with the announcement that Pamela’s was shuttering its iconic Squirrel Hill diner location.

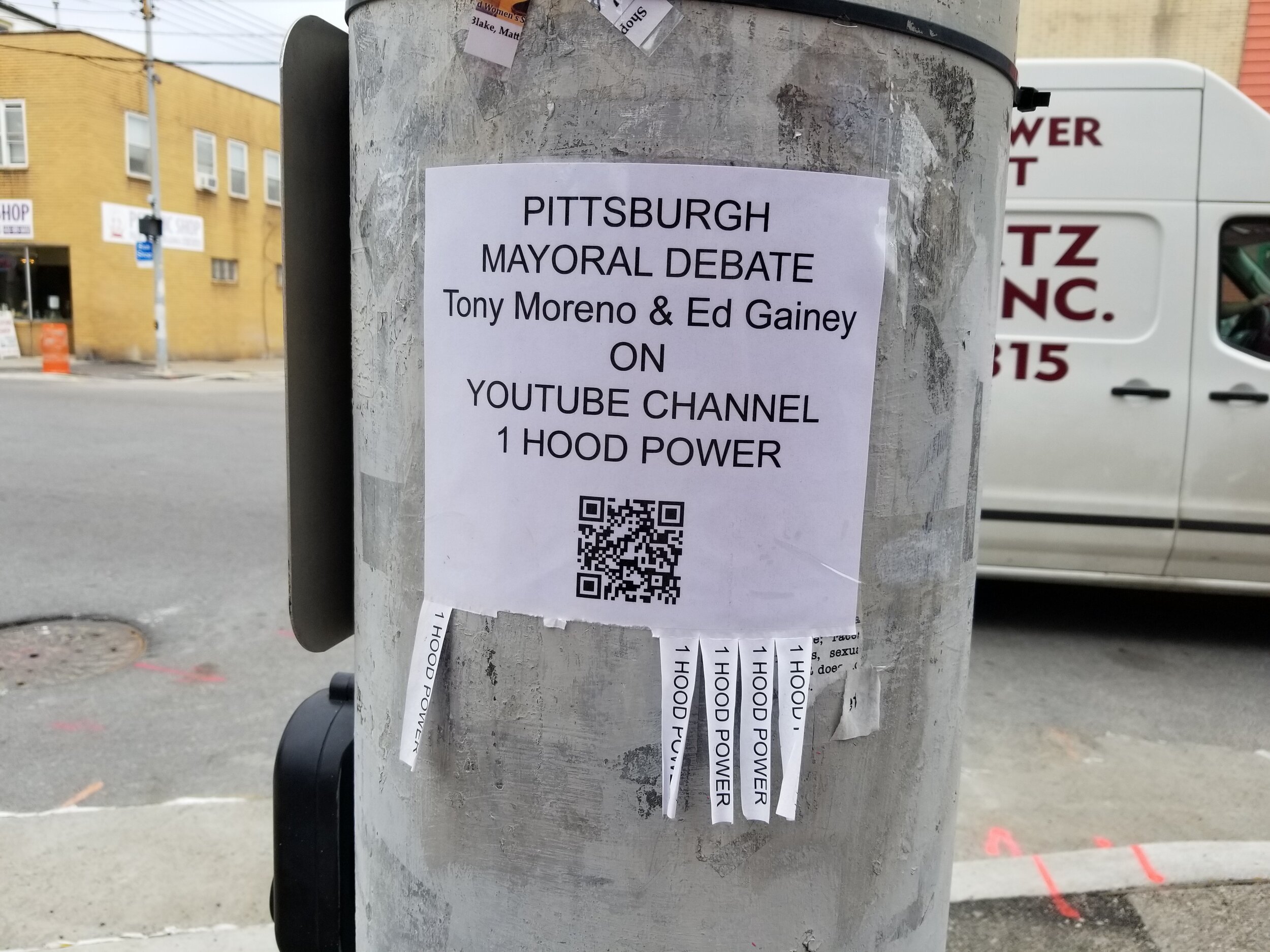

The long tail of the pandemic and the pervasive encroachment of gentrification will continue to remake the landscape of Pittsburgh, just as they are shaping cities around the world. But this new year also marks a political shift in the city. Today (January 3rd) Ed Gainey will be inaugurated as the 61st mayor of Pittsburgh and the city’s first mayor of color. Over the past weeks there have been numerous reflections and retrospectives on the legacy of outgoing mayor Bill Peduto. For me, Peduto’s mayoral tenure will always be associated with mobility and infrastructure. Not only did his administration create the Pittsburgh Department of Mobility and Infrastructure, but these were central focal points for my research into neighborhood change and development in the city over the last several years.

The final year of Peduto’s term saw further inroads in transit policy and innovation. Last July the city launched Move PGH, which was touted as the country’s first transit app for non-car transportation. The new initiative was accompanied by the introduction of e-scooters onto Pittsburgh’s streets, part of a comprehensive approach toward making the city a “leader in car-free mobility.” The fleet of electric scooters soon became an ubiquitous presence in Pittsburgh and sparked a rash of complaints over where the vehicles were being ridden or abandoned on city streets and sidewalks. Local media began covering scooter sightings on highways and in tunnels. As with the introduction of autonomous vehicle testing on the city’s streets years earlier, the Pittsburgh city council had to explore ways of legislating and regulating the new transportation technology.

In August a transit report ranked Pittsburgh the third-best 15-minute city in the country. The 15-minute metric refers to the availability of daily necessities and amenities within a 15-minute walk or bike trip. The study also highlighted the impact of affordable housing on mobility and accessibility, echoing a recent report that linked public transit funds to racial equity. That same month census data revealed that Allegheny County saw its first population growth since 1960, while also providing further statistical support for the much-discussed displacement of Black residents from Pittsburgh.

In September the Peduto administration announced the 2070 Mobility Vision Plan, a framework for the next 50 years of infrastructure investment in the city along with a commitment to “mobility justice.” The announcement of the vision plan was preceded by a host of new and proposed transit initiatives from the Pittsburgh Port Authority. The latter half of 2021 brought numerous other transit-related developments in the city including debate over the impact that a proposed Amazon distribution center would have on the streets of Lawrenceville, and a grant to transform a section of South Side’s 21st Street into a “complete green street.”

The closing month of 2021 saw a final flurry of mobility moves in Pittsburgh. Mayor Peduto announced plans to transform an abandoned road behind Bakery Square into a “living street,” with visualizations of the re-imagined streetscape. Residents of Hazelwood received news of a long-awaited sidewalk improvement, while mayor-elect Gainey announced a pause on the Mon-Oakland Connector that has long featured in debates over the remake-formerly-known-as-Almono that has been incrementally emerging in Hazelwood. Also in December, the city passed new legislation that bans parking in designated bike lanes.

All of these mobility-related initiatives are “on brand” for the Pittsburgh identity that Peduto has promoted during his term, but the bike lane legislation is a particularly appropriate measure for his final days in office. As I’ve mentioned before, bike lanes took on a distinct symbolic resonance in the mayor Peduto era. The newly dedicated lanes and other cycling infrastructure became synecdoches for the generational culture wars: bike lanes were regularly mentioned in letters-to-the-editor and the comment sections of local news websites as Pittsburghers decried a perceived shift away from traditional Steel City values toward the lifestyle preferences of the hipster-millenial-industrial-complex. While my own political values were typically at odds with the spirit in which bike lanes were cited in these cases, there is a germ of truth in what these Pittsburghers were responding to: bike lanes have been mobilized by municipalities as attractors for members of the “creative class,” and the social disparities inherent to “walkability” and “complete streets” rhetoric have long been noted. Indeed, my main contention with Peduto’s tenure hinges upon an overreliance and uncritical acceptance of “creative class” development initiatives (in conjunction with a pervading ethos of hegemonic liberalism that often expressed the right sentiments while falling short of inscribing them into policy).

This inherent ideological antagonism between the residual imaginaries of Pittsburgh’s gritty industrial heritage and the glossy banalized tech-sector landscape that has taken its place was aptly captured in a Pittsburgh Post-Gazette editorial published on New Year’s Day. Aside from correctly identifying the dominant contrasting urban identities that characterized Peduto’s mayoral term, the editorial seems ambiguously ambivalent toward the outgoing mayor (the conclusion is that Peduto was good for Pittsburgh but could’ve been better?). The compromised tone of the editorial may indeed be the result of a compromise among staffers: the Post-Gazette editorial board has long been highly suspect if not entirely disreputable due to the nefarious and noxious influence exerted by its right-wing ownership, but it seems that the editorial board will also be changing in the new year.

Mayor Peduto has given several interviews recently, reflecting on his accomplishments in office with a considerable degree of candor (I want to especially recommend this excellent write-up from Public Source). In one such reflection Peduto said that he might be remembered as “a bridge over troubled water.” It’s such a perfect cap to Peduto’s history of on-brand messaging rhetoric, drawing upon the bridges with which Pittsburgh is so closely identified as well as the emphasis on mobility and infrastructure that he foregrounded as mayor. It occurred to me this week that Peduto was first sworn in as Pittsburgh mayor in 2014, the same year that I arrived in the city. I remember watching his episode of Undercover Boss later that year. His approach to governance and vision of the city that he put forth has been integral to my experience of Pittsburgh.

Moving forward, and as long as I remain in Pittsburgh, I will continue to track the unfolding patterns of neighborhood change and development strategies, particularly as they relate to both old and new mobility infrastructure initiatives. Some of the ongoing infrastructure investments I am most interested in are not necessarily driven by transportation. For instance, Peduto’s “Dark Sky initiative” to combat light pollution by replacing 35,000 streetlights with LEDs. And more recently the Pittsburgh City Council approved the designation of six greenways to become city parks, a move that among other things addresses the importance of urban greenways in a post-pandemic world.

Incoming mayor Gainey has reasserted his commitment to a more diverse and inclusive Pittsburgh. As I’ve stated before, I am excited for this new era of civic leadership in the city, while also anxious about the racist rhetoric (whether explicit or implicit) that will surely emerge in public discourse during Gainey’s tenure. I wonder what will replace “bike lanes” as the metonymic signifier for competing cultural values and ideological struggles in the coming years.