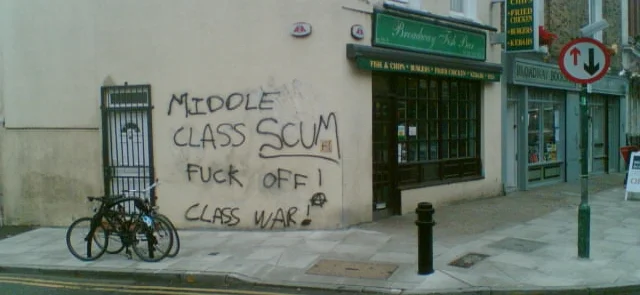

Gentrification: What's in a name?

Joe Saunders, Wikimedia Commons

- Writing for The Washington Post, Emily Badger argues that "it's time to give up the most loaded, least understood word in urban policy: gentrification":

The definition matters, in other words, not purely for linguistic nit-picking, but because we seldom talk about gentrification in isolation. More often, we're talking about its effects: who it displaces, what happens to those people, how crime rates, school quality or tax dollars follow as neighborhoods transform. And if we have no consistent way of identifying where "gentrification" exists, it then becomes a lot harder to say much about what it means.

This is all very academic, but there's a corollary lesson for laymen: Whatever point you're making about "gentrification" is undermined by the fact that the word has no clear, singular meaning.

- Badger cites a recent post by Richard Florida at CityLab that suggests "no one's very good at correctly identifying gentrification":

It's clear that "gentrification" is still a vague, imprecise and politically loaded term. We not only need better, more objective ways to measure it; we need to shift our focus to the broader process of neighborhood transformation and the juxtaposition of concentrated advantage and disadvantage in the modern metropolis.

- Reporting on a recent symposium on gentrification that took place in Philadelphia, Sandy Smith at Next City addresses the problem of definition while suggesting 3 ways communities can take control of gentrification:

The panelists who participated in a discussion on “Gentrification, Integration and Equity,” hosted by Next City on Dec. 3rd, had definitions that varied widely, and not all of them agreed that it was a bane. But the issue of better-off residents moving into low-income neighborhoods, no matter how one defines or slices it, does call for cities and communities to come up with ways to counter the ill effects and develop alternative, inclusive visions for redevelopment.

- Meanwhile, Pete Saunders at The Corner Side Yard has identified the types of gentrification:

Spurred on by the recent debate on the impact of limited housing supply on home prices and rents, thereby "capping" gentrification, (taken on fantastically by geographer Jim Russell in posts like this), I decided to do a quick analysis of large cities and see how things added up. The analysis was premised on a couple observations of gentrification, one often spoken and one not. One, gentrification seems to be occurring most and most quickly in cities that have an older development form, offering the walkable orientation that is growing in favor. Two, gentrification seems to be occurring most and most quickly in areas that have lower levels of historic black populations.

- The Guardian recently profiled Jan Gehl and "his battle to make our cities liveable"; Oliver Wainwright considers this approach to "liveable" cities and asks, "will all our cities turn into 'deathly' Canberra?":

Canberra is a deathly place. It is a city conceived as a monument to the roundabout and the retail park, a bleak and relentless landscape of axial boulevards and manicured verges, dotted with puffed-up state buildings and gigantic shopping sheds. It is what a city looks like when it is left to politicians to plan.

[...]

It is neither a new nor unusual phenomenon, but this year it proves to be particularly timely: the term gentrification was coined exactly 50 years ago, in the prescient writings of Marxist sociologist Ruth Glass. “London may acquire a rare complaint,” she wrote in 1964, after studying the rapid change of places like Notting Hill and Islington, from neighbourhoods of blue-collar workers to desirable havens for the middle-class urban gentry. “[The city] may soon be faced with an embarras de richesses in her central area – and this will prove to be a problem.” The idea of the inner-city becoming desirable and overpriced was unthinkable at the time. But 50 years on, we have exceeded her worst nightmares.