Urban Communication: media infrastructure, neighborhood narratives, rhetoric & rebranding, and more

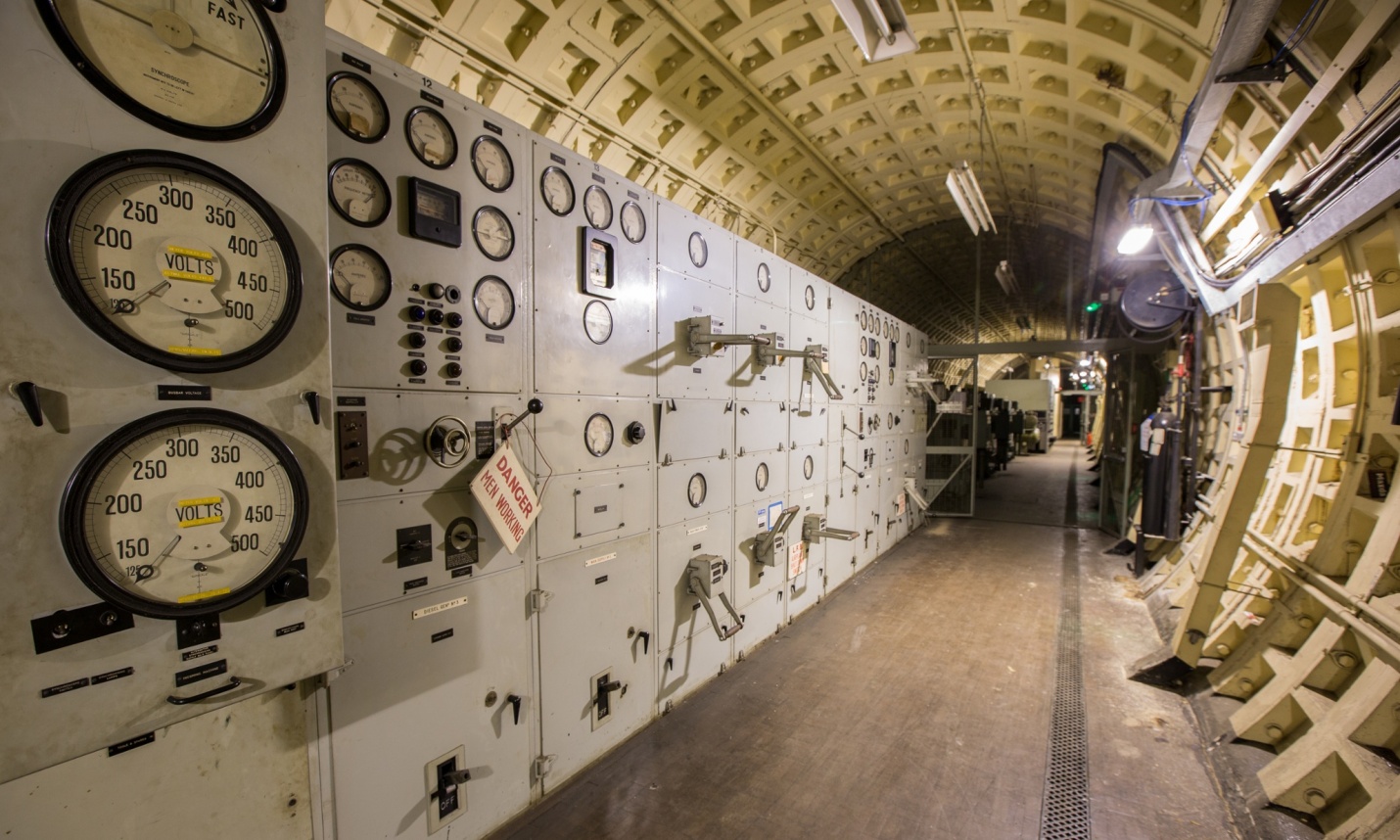

Kingsway Telephone Exchange, photo by Bradley Garrett, retrieved from <http://tinyurl.com/q54z46r>

- In Urban Media Ecology news, several recent studies reported correlations between characteristics of the built environment and human health. A study from the University of Kansas (in my birthplace of Lawrence) found that "neighborhoods that motivate walking can stave off cognitive decline in older adults":

The researcher judged walkability using geographic information systems — essentially maps that measure and analyze spatial data.

“GIS data can tell us about roads, sidewalks, elevation, terrain, distances between locations and a variety of other pieces of information,” Watts said. “We then use a process called Space Syntax to measure these features, including the number of intersections, distances between places or connections between a person’s home and other possible destinations they might walk to. We’re also interested in how complicated a route is to get from one place to another. For example, is it a straight line from point A to point B, or does it require a lot of turns to get there?”

Watts said easy-to-walk communities resulted in better outcomes both for physical health—such as lower body mass and blood pressure—and cognition (such as better memory) in the 25 people with mild Alzheimer’s disease and 39 older adults without cognitive impairment she tracked. She believes that older adults, health care professionals, caregivers, architects and urban planners could benefit from the findings.

- Another research paper from researchers at multiple institutions "suggests that street design may have a larger impact on public health than previously thought":

By studying 24 California cities with an array of street design characteristics and their associated health data, the authors find that living in cities with high intersection density—a measure of compactness—significantly reduces the risk of obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease. A full-grid street pattern also is a factor in lower risk of obesity, high blood pressure, and heart disease, as compared with full treelike patterns.

- At CityLab, Richard Florida posted a roundup of recent research studies on the health benefits afforded by walkable communities:

If walkability has long been an “ideal,” a recent slew of studies provide increasingly compelling evidence of the positive effects of walkable neighborhoods on everything from housing values to crime and health, to creativity and more democratic cities.

[...]

Walkability is no longer just an ideal. The evidence from a growing body of research shows that walkable neighborhoods not only raise housing prices but reduce crime, improve health, spur creativity, and encourage more civic engagement in our communities.

- Another CityLab article by Emily Von Hoffman looked at what architecture is doing to your brain:

I spoke with Dr. Julio Bermudez, the lead of a new study that uses fMRI to capture the effects of architecture on the brain. His team operates with the goal of using the scientific method to transform something opaque—the qualitative “phenomenologies of our built environment”—into neuroscientific observations that architects and city planners can deliberately design for. Bermudez and his team’s research question focuses on buildings and sites designed to elicit contemplation: They theorize that the presence of “contemplative architecture” in one’s environment may over time produce the same health benefits as traditional “internally induced” meditation, except with much less effort by the individual.

- As part of a directed study this semester, I've been studying the role of communication infrastructure in urban design, and particularly the parallel developments of mass media and the modern metropolis. Urban explorer Bradley Garrett recently wrote a piece for The Guardian about the massive infrastructure of underground London, including not just tube stations but communication infrastructure including Britain's deepest telephone exchange:

The urban exploration crew I had worked with, the London Consolidation Crew or LCC, had long graduated from ruins and skyscrapers – it was the city in the city they were after, the secrets buried deep underground where the line between construction site and ruin is very thin indeed. The Kingsway Telephone Exchange was the crème de la crème, more coveted even than abandoned Tube stations or possibly even the forgotten Post Office railway we accessed in 2011.

Kingsway was originally built as a second world war air-raid shelter under Chancery Lane. These deep level shelters were, at one time, connected to the Tube and citizens would have undoubtedly taken refuge here during Luftwaffe bombing runs. In 1949 the tunnels were sold to the General Post Office where they became the termination for the first submarine transatlantic phone cable – the £120m TAT1 project. The system, meant to protect the vital connective tissue of the city in the event of terror-from-the-air (including nuclear attack), stretched for miles. It only had three surface entrances and contained a bar for workers on their off-hours, rumoured to be the deepest in the UK at 60m below the street. Although the government employed a host of people to maintain the tunnels, Kingsway was a spatial secret of state - part a trio of the most secure and sensitive telephone exchanges in Britain, along with the Anchor Exchange in Birmingham and the Guardian Exchange in Manchester.

- These photos of subterranean communication infrastructure contrast with images of above ground cables covering the urban landscape, as featured in this io9 post, "photos from the days when thousands of cables crowded the skies":

Before most cables ran underground, all electrical, telephone and telegraph wires were suspended from high poles, creating strange and crowded streetscapes. Here are some typical views of late-19th century Boston, New York, Stockholm, and other wire-filled cities.

Wires over New York, 1887, via Retronaut, retrieved from <http://tinyurl.com/kb9dns2>

- Joseph Stromberg at Vox recently wrote about the "forgotten history of how automakers invented the crime of 'jaywalking'":

Auto campaigners lobbied police to publicly shame transgressors by whistling or shouting at them — and even carrying women back to the sidewalk — instead of quietly reprimanding or fining them. They staged safety campaigns in which actors dressed in 19th century garb, or as clowns, were hired to cross the street illegally, signifying that the practice was outdated and foolish. In a 1924 New York safety campaign, a clown was marched in front of a slow-moving Model T and rammed repeatedly.

This strategy also explains the name that was given to crossing illegally on foot: jaywalking. During this era, the word "jay" meant something like "rube" or "hick" — a person from the sticks, who didn't know how to behave in a city. So pro-auto groups promoted use of the word "jay walker" as someone who didn't know how to walk in a city, threatening public safety.

- William Eric Rinehart at Sweet Talk asks: Did a change in rhetoric give rise to cities?

Between the mega-village and the cities that came later lies the formation of the state. Ultimately, this is the world of stratification buttressed through religion. With it came the creation of differing social groups and distinctions based upon rank or property. Yet, the acceptance of social specialization required a new view of the world, a new rhetoric in the McCloskeyian sense. And once that jump was made, benefits followed. Clustered people allowed for more trade and specialization of work, leading to more wealth, prestige and better equipped armies. While still a brutal world, cities had the potential for stability, but it came at the expense of radical equality.

- Matt Stroud at The Verge recently wrote about the dream and the myth of the paperless city in Chicago:

But you can’t just flip a switch to reverse paper systems in place for hundreds of years, can you? Adobe first released its Portable Document Format nearly 20 years ago, yet many private companies, nonprofit organizations, libraries, law firms, courts — and yes, major city governments such as Chicago’s — have yet to embrace a world reliant on PDFs and devoid of paper records. Mayor Emanuel has agreed to change that. Or at least to try. In 2011, he announced plans to spend $20 million on efficiency improvements including changes to make the city less reliant on paper.

Will Mayor Rahm Emanuel change the way governments deal with paper? Or is the road toward a “completely paperless” government a long way off?

- At URBACT, Stefan Höffken and Chris Haller consider urban planning and the multi-dimensional communication era:

"Because urban planning has always been based on the gathering and exchange of information and – as a democratic process – on communication between different stakeholders, a change in the method of communication has a significant impact on decision-making throughout the process"

[...]

The quote at the beginning of this post was taken out of a paper by Stefan Höffken and Chris Haller, who set out to research how new medias were used for urban planning matters. They are refering to geographer Manuel Castells’ and Clay Shirky‘s work to describe the change from uni-dimentional communication towards a many-to-many exchange sphere that, so Shirky, is on the verge of becoming ubiquitous. Höffken and Haller provide interesting insights in how different tools can serve certain goals and complement each-other by surveying urban projects and institutions or civil society mobilizations on urban matters as different as Tulsa municipality and the Mediaspree campaign in Berlin.

- Emily Badger at the Washington Post reports that Uber is offering cities an olive branch in the form of their customers' trip data:

The company plans to partner first with Boston, sharing quarterly anonymized trip-level data with the city in a model that Uber says will become its national data-sharing policy. The data will include date, time, distance traveled and origin and destination locations for individual trips, identified only by zip code tabulation area to preserve privacy. Once held by cities, this information will be open to records requests, meaning that the public (and researchers) will have access to it, too.

Such data could help cities keep tabs on Uber and, for example, which neighborhoods the company is serving. Uber says, though, that it's primarily offering the data so that cities can better understand themselves.

A redesigned Los Angeles parking sign, retrieved from <http://tinyurl.com/nu5tr2z>

- Rosie Cima at priceonomics recently wrote about a designer's war on misleading parking signs:

Sylianteng first tried to redesign parking signs when she was living in LA and applying to grad school, in a project she called “To Park or Not to Park.” She reduced the usual jumble of signs and regulations to a single, holistic panel, which looked a lot like a Google Calendar – it was a grid of days of the week, broken into hours. The blocks of time when a parking spot was valid she shaded green, the blocks of time it was invalid she shaded red. She also simplified the rules she illustrated, working off the principle that people would much rather adhere to an overly restrictive regulation than get a parking ticket.

[...]

Her prototypes provoked a lot of commentary, discussion, and praise. She used this feedback to improve her designs. She printed out new prototypes, and taped those up. The feedback validated some of her central assumptions, among them: (1) a lot of current parking signs were very confusing, and (2) people didn’t care why they could or couldn’t park somewhere, they just didn’t want to be ticketed.

- At Tropics of Meta, South El Monte Arts Posse posted about mapping community narratives in El Monte and South El Monte:

The writing of social history needs to keep in mind the motivations and individual agency of the people participating in events as they happen. In interview after interview, people were aware of the larger structural forces, and yet made choices and actions in contradiction to expectations. Again and again we spoke with people who beat the odds, who pushed back against racism, and took it upon themselves to change circumstances and in many cases succeeded.

- Arwa Mahdawi at The Guardian reports on neighborhood rebranding in London:

Similar semantic shifts are being attempted, with varying degrees of success, throughout the rest of London. Intrepid developers have discovered “Tyburnia”, an undervalued stretch of real estate between Paddington Station and Hyde Park. Meanwhile, the “Knowledge Quarter” is an attempt to rid King’s Cross of its association with prostitution by emphasising the new preponderance of cerebral institutions there. You could call it “brain-washing”. The Knowledge Quarter, incidentally, is one of 21 “Quarters” in London; there are also a dozen or so new “Villages”. Neighbourhood rebranding is often the linguistic leg of gentrification and, as such, follows a predictable pattern: “Villages” assert their legitimacy by emphasising community, while “Quarters” lend a gravitas to whatever noun they follow. Both have a cleansing effect on the associations that came before them.

- At NextCity, Nathan C. Martin considers why art, not Google, could revolutionize WiFi:

Remember a few years ago when television went digital and everyone had to get adapters or new TV sets? When that happened, what once were television channels became simply channels, a bulk of empty bandwidth that could host any variety of transmission. The Federal Communications Commission named it Super WiFi. The policies to regulate it are yet to be written, and a chorus is imploring the FCC to leave a large part of the spectrum open, or “unlicensed,” instead of auctioning it off. Those advocates tend to refer to the spectrum in spatial terms — a group of Stanford University economists likened the spectrum to a public park, a resource everyone should have access to. Mary Ellen Carroll speaks of it similarly. “It’s like public land,” she says. “It’s like Yosemite.”

- Finally, Emanuel Maiberg at Motherboard looks at homelessness in SimCity, and whether it is a bug or feature:

SimCity's homeless people are represented as yellow, two-dimensional, ungendered figures with bags in tow. Their presence makes SimCity residents unhappy, and reduces land value. Like many other players, Bittanti discovered the online discussions when he was searching for a way to deal with them.

At first, players wondered if they were having so much problems with the homeless in their cities because of a bug in the game. Like many of 2014's big-budget games that launched in broken or barely-functional states, SimCity originally would only work if players connected to EA's servers, which repeatedly crashed under the load of players. It seemed possible that the homeless problem in SimCity was simply a mistake.

"Has anyone figured out a easy way to handle the homeless ruining those beautiful parks you spend so much money on?" asks one player on EA' site. "Create jobs, either through zoning or upgrading road density near industry, that helped me a lot," another player suggests.