The researcher judged walkability using geographic information systems — essentially maps that measure and analyze spatial data.

“GIS data can tell us about roads, sidewalks, elevation, terrain, distances between locations and a variety of other pieces of information,” Watts said. “We then use a process called Space Syntax to measure these features, including the number of intersections, distances between places or connections between a person’s home and other possible destinations they might walk to. We’re also interested in how complicated a route is to get from one place to another. For example, is it a straight line from point A to point B, or does it require a lot of turns to get there?”

Watts said easy-to-walk communities resulted in better outcomes both for physical health—such as lower body mass and blood pressure—and cognition (such as better memory) in the 25 people with mild Alzheimer’s disease and 39 older adults without cognitive impairment she tracked. She believes that older adults, health care professionals, caregivers, architects and urban planners could benefit from the findings.

By studying 24 California cities with an array of street design characteristics and their associated health data, the authors find that living in cities with high intersection density—a measure of compactness—significantly reduces the risk of obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease. A full-grid street pattern also is a factor in lower risk of obesity, high blood pressure, and heart disease, as compared with full treelike patterns.

If walkability has long been an “ideal,” a recent slew of studies provide increasingly compelling evidence of the positive effects of walkable neighborhoods on everything from housing values to crime and health, to creativity and more democratic cities.

[...]

Walkability is no longer just an ideal. The evidence from a growing body of research shows that walkable neighborhoods not only raise housing prices but reduce crime, improve health, spur creativity, and encourage more civic engagement in our communities.

I spoke with Dr. Julio Bermudez, the lead of a new study that uses fMRI to capture the effects of architecture on the brain. His team operates with the goal of using the scientific method to transform something opaque—the qualitative “phenomenologies of our built environment”—into neuroscientific observations that architects and city planners can deliberately design for. Bermudez and his team’s research question focuses on buildings and sites designed to elicit contemplation: They theorize that the presence of “contemplative architecture” in one’s environment may over time produce the same health benefits as traditional “internally induced” meditation, except with much less effort by the individual.

- As part of a directed study this semester, I've been studying the role of communication infrastructure in urban design, and particularly the parallel developments of mass media and the modern metropolis. Urban explorer Bradley Garrett recently wrote a piece for The Guardian about the massive infrastructure of underground London, including not just tube stations but communication infrastructure including Britain's deepest telephone exchange:

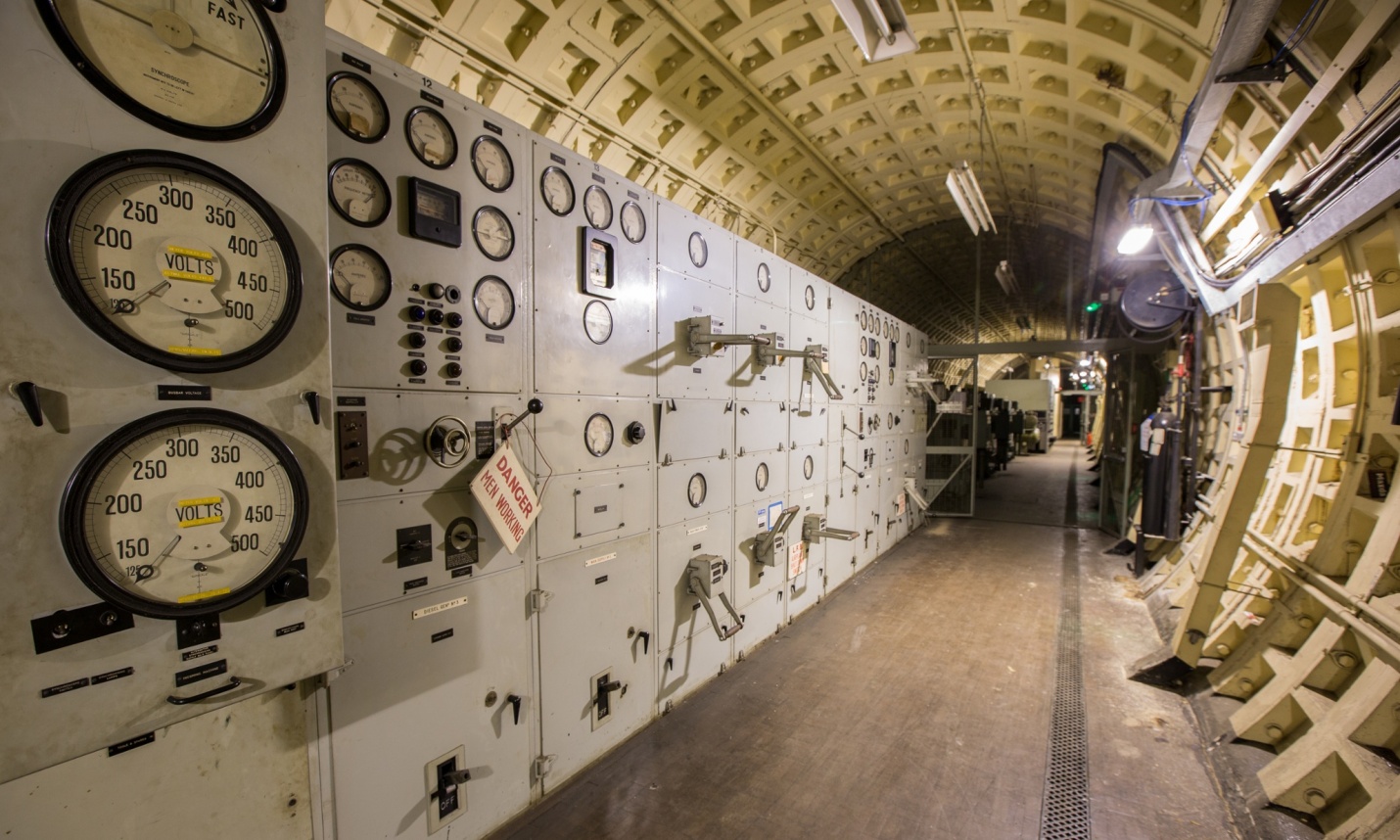

The urban exploration crew I had worked with, the London Consolidation Crew or LCC, had long graduated from ruins and skyscrapers – it was the city in the city they were after, the secrets buried deep underground where the line between construction site and ruin is very thin indeed. The Kingsway Telephone Exchange was the crème de la crème, more coveted even than abandoned Tube stations or possibly even the forgotten Post Office railway we accessed in 2011.

Kingsway was originally built as a second world war air-raid shelter under Chancery Lane. These deep level shelters were, at one time, connected to the Tube and citizens would have undoubtedly taken refuge here during Luftwaffe bombing runs. In 1949 the tunnels were sold to the General Post Office where they became the termination for the first submarine transatlantic phone cable – the £120m TAT1 project. The system, meant to protect the vital connective tissue of the city in the event of terror-from-the-air (including nuclear attack), stretched for miles. It only had three surface entrances and contained a bar for workers on their off-hours, rumoured to be the deepest in the UK at 60m below the street. Although the government employed a host of people to maintain the tunnels, Kingsway was a spatial secret of state - part a trio of the most secure and sensitive telephone exchanges in Britain, along with the Anchor Exchange in Birmingham and the Guardian Exchange in Manchester.

Before most cables ran underground, all electrical, telephone and telegraph wires were suspended from high poles, creating strange and crowded streetscapes. Here are some typical views of late-19th century Boston, New York, Stockholm, and other wire-filled cities.